Editor's Note: It’s a new year and a new faiV. I’ll try not to dwell on what precedes that famous line, nor will I spend a lot of time on explanations or apologies. I will note that the gap between this faiV and the last one is 30% smaller than the previous hiatus. But I figured there was limited time to write a few more faiVs before being replaced by Claude Code. The plan for this part of the cycle is to go to twice monthly, with me (Tim) writing once per month and Jonathan and Laura handling the other one. Also of note, we will be shifting away from Mailchimp imminently so stay tuned for details on shifting your “subscription.”

- Tim Ogden

1. Volatility Validated

We’re in the 10-year anniversary window (we started publishing data at the end of 2014, the book came out in 2017) of the US Financial Diaries. I think it’s fair to say that the core finding was much higher rates of income volatility among lower-income American households. While we were confident in what we saw in our data, it was not a nationally (much less internationally) representative sample, and high-frequency data collection is mechanically going to pick up at least some higher level of volatility than other methods. Being good Bayesians, we had to maintain some level of uncertainty about whether such high income volatility would show up in larger samples and in administrative data.

So it’s been gratifying to see a series of papers recently that validate the volatility we saw is there and a major factor in low-income households' financial lives. First, here’s Ganong et al. using a large administrative data set in the US to show that “earnings instability is pervasive…[and] unequally distributed: lower-income, hourly workers face more instability.” And there’s more: “it increases consumption volatility…workers have a high willingness to pay to reduce [it]." Meanwhile, Brewer et al. find meaningful month-to-month earnings volatility in the UK among the bottom 10% of earners, and Andresen et al. find that in Norway that a quarter of job-months have a 23% change in income (while only just over a quarter have no change).

Income volatility is a real phenomenon in industrialized economies with formal jobs, and that has major implications for how we think about the challenges facing low-income households, and even how we think about how to measure poverty and what it means to be poor.

2. New-ish at FAI-ish

Poverty at Higher Frequency (measures) is something that Jonathan and Josh Merfeld have been thinking and writing about—expect to hear more about that in the next edition of the faiV.

Meanwhile, as a team we’ve mostly been focused on Small Firm Diaries, globally, and now Small Firm Diaries USA. There’s a new issue brief about the challenges that small firms face based on the global data. Completely unrelated to the project, here’s Grady Killeen’s job market paper finding that fear of short-term losses among small Kenyan retailers has an effect on growth (Stability Entrepreneurs!).

We took advantage of the Small Firm Diaries in Fiji to run a parallel project about a long-standing question I’ve had: household finances of transnational households. In other words, how does having someone from the household emigrating to another country and sending home remittances affect both the migrant and the sending household? (See also, urban-to-rural migration and remittances). Ryan Edwards and Estelle Stamboulie have a first pass working paper looking at the data and finding that migrants try to send a stable amount home, but when there are meaningful negative shocks (volatility!) those get passed along to the family back home.

On the U.S. side, we have a running blog (yes, those still exist!) with a recent focus on the very confusing state of the data about small businesses and employment in the U.S., and we had a faiVLive looking at some very early data from the project.

3. Gambling

If you pay any attention to sports in the U.S., it is impossible to miss how much the legalization of sports betting has changed the landscape (cf. “You don’t really watch basketball anymore. You watch micro-events resolve.”). If you pay any attention to finance, it’s impossible to miss the growth of prediction markets. One of Matt Levine’s newsletters this week was almost entirely about how prediction markets and gamified gambling are taking over finance. If you pay any attention to household finance, it should be impossible not to be terrified where all of this is leading.

But if this is not on your radar, legal online sports betting increases credit card debt and overdrafts among low-income households. Legalizing sports gambling was a huge mistake. Smartphone gambling is a disaster. People are losing huge sums, and problem gambling is skyrocketing. But sometimes the best way to drive home the issue is comedy, to hide the crying.

4. Household Finance, Systems, Regs and Measures

A specific thing to pay attention to is the degree to which people’s vulnerability to gambling can be quantified and exploited. Online sportsbooks and casinos are already doing this at scale—figuring out who is most vulnerable and exploiting them while kicking out the very small number of people who win. It’s the “big new way to get rich” (no, not gambling, preying on people who do it).

This is clearly very bad. But it’s not just limited to gambling, and it's very hard to figure out how to regulate systems to prevent such bad behavior when it’s possible to collect and efficiently analyze so much data on individuals. John Campbell and Tarun Ramadorai have a new book (it’s on its way, I haven’t read it yet) on how even well-intentioned financial system regulations essentially become transfers from the vulnerable to the savvy. Ramadorai gave a talk on this at AEA last week; here’s Campbell giving a talk this fall. There's a specific overlap that I find interesting (and see the Image of the Day, below) that I'll plan on returning to in future faiVs but pointed to here by Conor Sen: the growth of the upper middle class in the U.S. is helping drive this phenomenon.

I was thinking about this while in an AEA session about measuring the unbanked and underbanked population in the U.S., and a specific presentation about the (under)use of digital payments. How do you measure whether someone is not using a digital payment system because it’s too expensive (per transaction cost) or too expensive (high risk of an invalid/fraud transaction being irreversible and not being able to compensate for it)? So much of the issue depends not just on the rules but the way they are implemented, and the second- and third-order effects of the way the rules are monitored. Here’s Patrick McKenzie writing about how Reg E (originally from 1979!) is being implemented, manipulated, and/or ignored in the rapidly changing electronic payments market in the U.S. Here’s David Porteous’ recent piece on who pays for electronic payments in developing markets (the Great Convergence!) and how forcing payment services providers to offer 0-cost payments has important second- and third-order effects (say, just spitballing here, like capping credit card interest rates at 10%).

5. Other Tabs

Those of you who still remember the faiV will suspect that I have a nearly infinite number of tabs open with items that I was saving to put in the faiV when I started writing again. You are wrong: it’s actually an infinite number of tabs. There are a few that I couldn’t bear to let slip away:

The Case for Counterfactual Thinking in Non-Profit Fundraising and a bonus link to a Planet Money episode about GiveWell (Reg FD: I'm board chair) trying to consider counterfactuals about filling USAID gaps in the absence of good data.

The Honesty Tax. This is a concept you'll hear me talk about a lot in the coming months in the context of Small Firm Diaries USA.

Can We Trust Social Science Yet? and a bonus link to Tracking the Credibility Revolution Across Fields.

And finally what we might call a "reading tax." This fall I had a piece in the Journal of Cell Science completely unrelated to faiV topics, but ultimately heavily influenced by my experience working with local organizations on field research projects, and perhaps you might find some useful thoughts: Engaging Patient-Led Rare Disease Organizations to Advance Research.

Image of the Day

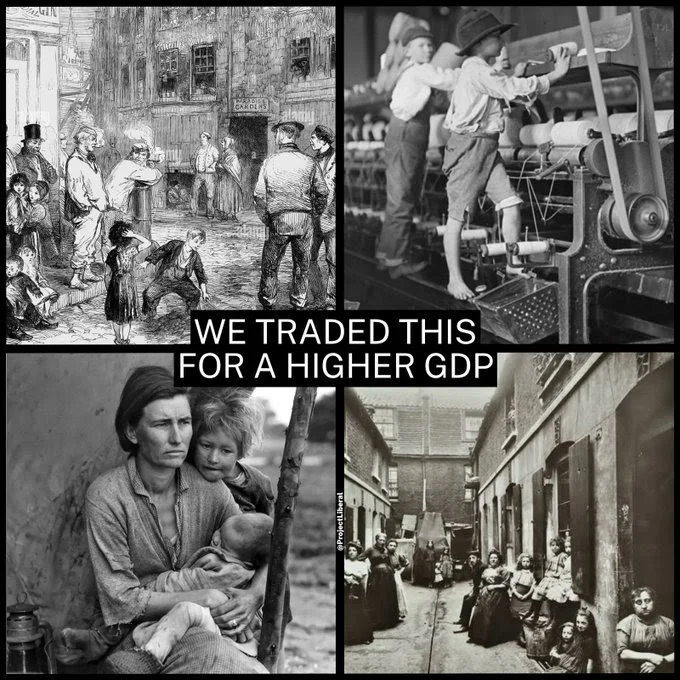

A helpful reminder about what we've lost, for now, and how much more there is still to do; and that I still pay attention to internet memes.

The faiV is written by Timothy Ogden and produced by the Financial Access Initiative at NYU's Wagner Graduate School of Public Service

Email: fai-wagner@nyu.edu

To read this in your inbox, subscribe to the faiV.