1. US Inequality: I talk a lot about congruence between the US and developing countries, but usually in the context of sharing lessons in the financial inclusion domain. But there are other domains where there is a lot more commonality. For instance radically corrupt policing. While this paper has been circulating for awhile, it's worth revisiting over and over again, and it's acceptance for publication is a convenient excuse. US cities and towns, when faced with budget deficits, ramp up arrests and fines of and property seizures from black and brown citizens but not white ones. Here's the easy to share Twitter thread version so you can send it to your not so economics-paper-inclined friends. To be clear, it's only second-order racism. The reason seems to be it's much easier to get away with stealing from people of color because of systemic racism.

Systemic racism like the premium that blacks pay for apartments, a premium that rises with the fraction white a neighborhood is. Lucky that the place you live has little effect on the quality of your education or your future job market opportunities. Oh, wait.

The US is still deeply segregated (cool visualization klaxon) and there has been virtually no progress on that front in decades. Part of the reason is exclusionary zoning which puts a floor on home prices well above the reach of black and brown households. Apparently though, the Department of Housing and Urban Development is planning on tying future grants to cities to cutting zoning restrictions on multi-family dwellings. That would be a rare bright light in the current administration's deregulation push.

2. Cash: I haven't done anything on cash transfers, universal, conditional or otherwise in quite a while. This week we got a flood. I'm going to try to cover the landscape first, before some summary thoughts. Blattman, Fiala and Martinez have an update on their cash grants to youth clubs in Uganda paper--the one that found large gains after four years. After nine years, the controls have caught up. Chris used the analogy of "a tightly coiled spring" as an explanation for why the gains in the first four years were so surprisingly large--and that analogy may still hold. No matter how high the spring jumps, it eventually returns to baseline. Here's Chris's Twitter thread on how his thinking has changed. Here's a Vox article by Dylan Matthews. At this point, if you pay any attention at all, you should expect Berk Ozler to have some thoughts. He does.

Meanwhile, IPA pulled off the greatest unintentional (I'm told by reliable sources--hi Jeff!) mass market advertisement for the release of a development economics working paper in history when the NYTimes Fixes column ran a long-delayed piece by Marc Gunther on using cash as a benchmark for development programs on Tuesday. The paper was being released Thursday. That paper, a comparison of a Catholic Relief Services program to a cost-equivalent cash grant, and a much larger cash grant, by McIntosh and Zeitlin is here. The IPA brief is here. The Vox article is here. And Berk's thoughts (about the Vox coverage really) are here. And Tavneet Suri's. But I'll give Craig and Andrew the last word--here's their post on Development Impact on how they think about the study and the issues.

Week of September 3, 2018

1. Social Investing: Calling out the bland and meaningless rhetoric in social and impact investing almost seems unsporting--it's just too easy but it's Friday after a long week so I'm going to do it anway. Take this piece from John Elkington, who coined the term "triple bottom line," (Please), saying it's time to "rethink" or "recall" or "give up on" it (all his phrases). Why? Because the term has been misunderstood and misappropriated for uses well short of what he intended. Instead he thinks we need "a triple helix for value creation, a genetic code for tomorrow’s capitalism." But apparently not a clear definition or a recognition of trade-offs under scarcity.

Then there's this piece from the Wall Street Journal on the meaninglessness of words like "ethical", "impact" and "sustainable" in the mutual fund world. It's a treasure for the sheer density of laugh out loud snippets. For instance, Deutsche Bank switched out the word "dynamic" in the title of a family of funds and replaced it with "sustainable." Vanguard's bar for a company being "socially responsible" is literally not enslaving people or manufacturing weapons banned by international treaty. But my favorite is probably this quote about buyers of "ESG" funds: "We do hear from investors that have bought funds that they never realized did something." (Protip for non-WSJ subscribers who may not otherwise take the trouble to read this gem, search the title in an incognito window, click on the result link and close the invitation to subscribe and you'll be able to read it.)

2. Household Finance, Part I, Theory: Not realizing that funds did something is a good transition to Matt Levine's musings about the relationship between financial services providers and customers (scroll down to "How much should an FX trade cost?"). Matt is writing specifically about investment and corporate banking but the theory fully applies. In short, 'smart' large customers treat banks like commodity providers and ruthlessly push margins toward zero. Banks have to go along because these are large customers and economies of scale matter in financial services. So the banks make up those margins by charging 'loyal' customers much more than 'smart' customers. Which is, shall we say, not what 'loyal' customers think the banks should be doing and they rightly get very angry when they find out. So loyal customers should be more like smart customers and treat banks like commodity providers. The application of faiV interest is the Catch-22 for lower-income households: they only very rarely have the time and choice to treat financial services like a commodity, so they are almost inevitably left subsidizing wealthier customers. And even banks with good intentions struggle to do otherwise, because if you don't have the large customers, you can't drive costs down through scale.

In other theory news, one of the common motivating theories on helping low-income households is helping them plan. Planning is hard when facing scarcity. There's been encouraging evidence of the value of specific planning for getting people to follow through on their intentions. Here's a new paper testing the value of planning for one of the only two intention-action gaps that can rival the intention-action gap on savings: exercise (the other being dieting). It finds that careful detailed planning of an exercise routine has a precisely zero effect on follow-through.

Finally, here's a piece that at face value seems to be talking about the empirical transition away from cash (in the US). But look closely and it's really musing on the theory about the costs of cashlessness for lower-income households, something that deserves a lot more attention, on theory and empirics, than we seem to be getting right now. And it features Lisa Servon and Bill Maurer so you should definitely click.

3. Household Finance, Part II, Practicum: I don't remember how I stumbled across this paper about how US households respond to high upfront medical costs. It's not new, but it was new to me, though I suppose you can also say it's very old to anyone who has paid attention to healthcare consumption in low-income countries. The authors find a large decrease in spending, but no evidence that households are price shopping or making any differentiation between high-value and low-value services. Something to think about--how much of what we call "shocks" for low-income households are actually "spikes" that they didn't have the tools and bandwidth to manage (liquidity) for?

Week of August 27, 2018

Editor's Note: I'm still playing catch-up this week, and perhaps you are too. It's the "end of summer" in the Northern Hemisphere after all, that week we all get to, in a panic, confront all those things we had put off to the Fall AND all those things we thought we would get done during the "less busy" summer. Catching up notwithstanding, this is a somewhat truncated edition of the faiV, as I head into a weekend of labor related to the above.--Tim Ogden

1. Small Dollar Financial Services: I've been doing a lot of reading the last few weeks about the history of consumer banking (Hi Julia!), and by history I mean going back to the Middle Ages and before. From that reading, it's clear that small dollar lending has always been the bane of the banking system--and there is nothing new under the sun (thanks, David Roodman!). Which certainly colors my view when I see stories about overhauling the overdraft system in the US. Not that I don't think there is room for significant improvement. Overdraft is perhaps the worst possible way to manage small dollar lending--by pretending it's something else while still charging exorbitant fees that would make many microfinance institutions blush. There are plenty of ideas, like this story on a non-profit payday alternative lender which charges roughly half the fees of its competitors. The intent of the story seems to be offering this as a real alternative, but the details keep getting in the way. The nonprofit really is nonprofit in the literal sense of the word, not even being able to pay its CEO a $60,000 per year salary regularly, and facing "four near-death experiences" in 9 years--that sounds about par for the course in small dollar lending from the historical record.

2. Algorithmic Overlords: Yuval Noah Hariri has a new piece in the Atlantic, the title of which is just candy-coated confirmation bias for me, so how could I resist putting it in the faiV: "Why Technology Favors Tyranny". I'm feeling validated that I started reading Asimov's I, Robot to my kids this week. But back to Hariri, two thoughts: a) borrowing a category from Tyler Cowen, this is a very interesting sentence: "At least in chess, creativity is already considered to be the trademark of computers rather than humans!", and b) the picture Hariri paints bears a remarkable resemblance to the Allende plan in Chile specifically, and to almost every example in Seeing Like A State, it's just that the technology is finally catching up to the political ideology. The big question, of course, is whether the technology will yield any better results.

One more item I couldn't resist is this piece about blockchain and supposed complacency toward technological innovation in development. The most important thing to know is that the two examples given of the benefits of a decentralized ledger (e.g. blockchain) are two of the most centralized and highly policed ledgers in existence: SWIFT and Visa payment networks. It continues with a few potshots at small dollar fintech lenders and then some ersatz blockchain evangelism about power to the people. Let's hope the author reads many of the pieces linked above, but especially Hariri's. And just because, here's a story about the very first blockchain hiding in an ad in the New York Times in 1995.

3. Methods and Evidence: You've likely seen the uproar over ridiculous nutrition studies (on alcohol and dairy--clearly the message is to only drink dairy-based cocktails this weekend) this week. I saw someone on Twitter commenting on how the credibility revolution seems to have passed right by nutritional epidemiology, probably because it would mean that no studies ever got published.

Part of the credibility revolution is the emphasis on open data and replication. Here's a report on the latest large scale replication effort (of 21 social science studies published in Nature and Science). Thirteen of the 21 were generally replicated, but the effect size was roughly half of that originally reported. Of course, this raises the question of what "successful replication" means again. Here's a Twitter thread from Stuart Buck of the Laura and John Arnold Foundation on the difficult distinction between failed replication being a part of the scientific learning process and a failed replication as part of identifying shady research and publishing practices.

Here's a troubling story about unreliable administrative data. The US Department of Education asked school districts to start reporting "school-related shooting" incidents. There were 240 reported. But follow-up reporting was only able to verify 11 of those incidents and 161 were explicitly denied. Don't let the emotional subject of school shootings distract entirely from the reminder that there are always problems with data gathered like this, no matter what the subject. And pause for a moment to remember that it is data like this that Hariri fears will be used to automate administrative regimes.

The point of these studies, whether ridiculous nutritional ones, or administrative-data based ones, is most often to influence behavior and policy. Here's Jean Dreze on the challenge of evidence-based policy, and the need for economists "to be cautious and modest when it comes to giving policy advice, let alone getting actively involved in 'policy design.'"

4. Global Poverty: On the topic of evidence-informed policy choices, one of the most hotly debated questions in the field right now is what is happening with global poverty. At face value it seems like this is just a question of going to look at the data. But as with so many other areas, different people see very different things in the data (even if it is accurate). It all depends on how you measure poverty and whether you care more about absolute or relative numbers. There was a glimmer of detente in this debate this week as Jason Hickel and Charles Kenny published "12 Things We Can Agree On About Global Poverty." But that only lasted a day before Martin Ravallion chimed in with this Twitter thread, which begins, "it seems they only agree on the obvious, and ignore some less obvious things that really matter."

If you're looking for another way into these debates and the various issues that arrive, here's a Washington Post story about Nigeria displacing India as home to the largest number of people in absolute poverty. Maybe.

5. Social Investment and Philanthropy: I highlighted a couple reviews of Anand Giridharadas' new book Winners Take All last week. Here's another, from Ben Soskis, which I include because it's the best one yet. The theme of Giridharadas' book (and Rob Reich's new book as well) is being skeptical of the power of large-scale philanthropy or social investment. Here's a thread from Chris Cardona, of the Ford Foundation, on the multitudes contained in the word philanthropy, which is certainly important to take into account when considering the critiques. But the question of who is a philanthropist, who is abusing their power, and the trade-offs of institutionalization of philanthropy are always messy. Here's a story about a viral GoFundMe campaign to help a homeless man in Philly who gave his last $20 to rescue a stranded motorist. If you have Calvinist sympathies like me, you'll probably guess what happened next. Finally, here's Ed Dolan of the Niskanen Center on whether we need the charitable deduction.

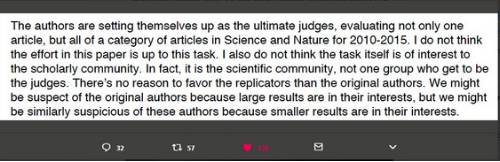

Returning to the topic of methods and evidence-based policy, two images popped up in my Twitter thread this week that I couldn't get out of my head. One is a snippet from a peer reviewer of the social science replication paper highlight above, explaining why it was not published in Nature or Science even though it was replications of papers from those journals. And second is a picture taken from a talk John List was giving this week about his career. You have to ask, does science advance via replication or via funerals? Via Brian Nosek and Ben Grodeck respectively.

Week of August 20, 2018

1. Financial Inclusion and Digital Finance: The last time I was writing the faiV, various takes on the Global Findex data were being featured prominently. So it only seems fitting to come back to that as I return. Greta Bull of CGAP has a two-part blog, part I and part II, reacting to Beth Rhyne's and Sonja Kelly's take (may I take a moment to smile at the inclusion that sentence reveals?) on the Hype vs. Reality of inclusion. Bull argues that the Findex data shows greater progress on inclusion than Rhyne and Kelly see. For what it's worth I lean to toward Bull in this debate. It would be surprising, given the incredibly rapid progress in access, if the access-use gap wasn't growing, especially in countries with relatively low levels or recent gains in access as network effects won't kick in for awhile.

There is another concern beyond the use/access gap--does use of the available accounts make people better off. Here's a new paper from Kast and Pomeranz showing that providing free savings accounts in Chile led to lower debt burdens (and some additional evidence on rotten kin). On the other hand here's an open letter from Anup Signh to Kenyan Central Bank governor Patrick Njoroge making the case for urgent regulatory action on digital credit to protect borrowers. On the third hand (hat tip to Brad DeLong) mobile money seems to have saved lives (note no counterfactuals there, but it seems plausible) during Ebola outbreaks in Liberia and Sierra Leone during Ebola outbreaks by ensuring that response workers got paid.

Of course, benefit depends not just on use, but on who is using the services. Microsave found that 80% of the "addressable LMI market" in India was not being served by fintechs, and, with CIIE's Bharat Inclusion Initiative, has launched a "Financial Inclusion Lab" to help Indian fintech's address that market.

2. Our Algorithmic Overlords: If you've gotten out of the habit of reading the faiV, what better way to grab your attention back than sexbots! Here's Marina Adshade, an economist at UBC, with a thoroughly economic argument about how sexbots could make marriage better (by changing how it works and what it does). And here's Gabriel Rossman, a sociologist at UCLA, making the counterargument. Apparently he reads Justin Fox.

On a much more prosaic, and more urgent, front, there have been a raft of stories on the increasingly alarming situation in Northwest China where the tech-driven panopticon seems to be racing ahead in the service of persecution of Muslims and ethnic minorities. Here is the NYTimes "inside China's Dystopian Dreams". Here's Reuters on the "surveillance state spread[ing] quietly." MIT Technology Review asks, "who needs democracy when you have data?" And here's Foreign Affairs on the "coming competition between digital authoritarianism and liberal democracy." If I have a bone to pick it's the lack of attention to the possibility of "authoritarian democracy" that comes along with a surveillance state and AI overlords.

3. Global Development: If sexbots don't get your attention, what about hyperselectivity of migrants? I think, quite a while ago, I linked to Hicks, et al. on the systematic differences between those who migrate from rural to urban Kenya, and those who stay on the farm, finding that urban productivity is a factor of the traits of the workers who migrate.

Week of August 6, 2018

1. Universal Basic Income (unpopular locale edition): In 2010, to replace massive energy and food subsidies, the Iranian government apparently implemented a cash transfer program that began covering over 95% of the population (75 million people) before targeting seems to have lowered coverage to less than 35 million. The story in two sentences: “In 2011, the first full year of the program, transfers amounted to 6.5% of the GDP and about 29% of the median household income. After three years of inflation, the amount transferred per person is down to less than 3% of GDP per capita.” New research finds minimal effects on labor supply or hours worked, though the short time horizon for the large transfers makes it hard to generalize. I suspect that the short time horizon is only part of the reason this policy hasn’t gotten more attention.

2. Our AI Overlords: Another AI benchmark falls. In a much-publicized practice event Sunday, an AI system developed by OpenAI beat a team of former pros at a mutliplayer video game called Dota (they had a livestream and posted a video that is totally inscrutable to me). This was expected given the rapidly-growing computation devoted to experiments like this, though it looks like the training required by this model (190 “petaflop/s-days,” whatever those are) was less than would be expected from extrapolating past large experiments. (The costs for those experiments are also growing by an order of magnitude every year and a half, which seems… unsustainable.) Apparently OpenAI are planning a Dota match against current pros later this month, so expect to hear more about this.

3. Cryptocurrency (or Weird Household Finance): Apparently “proxies for investor attention strongly forecast cryptocurrency returns,” which seems… a little obvious? And Matt Levine discovers a subculture of people who intentionally participate in pump and dump schemes in marginal cryptocurrencies as a form of gambling, which raises the question - what do the other people investing in marginal cryptocurrencies think they are doing?

The First Week of August, 2018

1. FinTech Charters: Just as the industry takes off for summer vacation, the US Treasury Department released its long-awaited fintech report and the OCC issued a call for fintech charter submissions. I’ve spent the past week sorting through scores of analyses and reactions. Here's American Banker on takeaways from the Treasury report and from the OCC's announcement. What does this mean for all things financial inclusion and innovation? Well, it certainly opens the door for many providers to expand their reach and their potential impact. It will likely be an expensive and involved path, but one that could ultimately give some fintechs much needed lift. However, this is still early in the game. I would expect to see lawsuits and challenges from incumbents now that the charter program is official.

2. Financial Stress and the Lunar Cycle: For many consumers, the end of the month represents constant instability as accounts are reduced to zero and bills become due. While income volatility is the umbrella issue, the specific actions that trigger this instability on a cyclical basis live both in our minds and in the products we use. One of our Entreprenuers-in-Residence, Corey Stone, tackles some big thinking on the topic in his series End of the Month. Drop in regularly to learn more about how human behavior can lead to suboptimal decision making, why long accepted product standards lead to this paucity of funds at the end of the month, and other insights into our monthly budgeting woes.

3. The Gig Economy: The difference between 4% and 40% is pretty significant. And the fact that the US Government doesn’t know how big the gig economy is, in short, a problem. To be fair, it’s not all the government’s fault. The variance in numbers can be attributed to a wide range of perceptions about what constitutes gig employment: full-time, part-time, etc. But no matter what the measurement, the impact is real. Gig employees enjoy the benefits of self-determination, but can often miss out on many of the benefits of traditional employment like insurance, savings vehicles, and more. The result can be regular cash flow gaps and challenging financial tradeoffs. To better design products and create guardrails, it’s imperative that we all find a better – more credible – way to measure this new workforce reality.

Week of July 23, 2018

1. Food Fights and Methods: First, over on the Economics That Really Matters blog, Paul Christian and Chris Barrett summarize their paper on US food aid and conflict. They call into question the results of an influential paper finding a causal link between US food aid and conflict. The authors follow up with a methodological note on the use of instrumental variables with panel data.

Next, the most recent issue of the American Journal of Agricultural Economics (AJAE) has a nice article, comment, and response. In the article Ore Koren finds that it is food abundance, rather than food scarcity, that causes conflict across Africa. Marshall Burke writes in a comment that the effect sizes are implausibly large and are at odds with previous research. Koren responds to these comments by offering three explanations for the "implausibly" large effect sizes.

2. Randomistas are our new Algorithmic Overlords: At the development economics section of the NBER Summer Institute, Esther Duflo delivered a lecture entitled, "Machinistas meet Randomistas: Some useful ML tools for RCT researchers". Slides from the lecture are available here, and Dina Pomeranz was live Tweeting the lecture. The paper it was based on is here. On the surface it may seem like machine learning and RCTs are interested in different parts of empirical research--the former focused on prediction and the latter focused on causal identification. Duflo highlights a couple areas where using machine learning when analyzing an RCT can be beneficial.

3. Informal Insurance: In a recent article on VoxDev, Kaivan Munshi and Mark Rosenzweig summarize some of the insights from their 2016 paper on the impact of rural informal insurance networks on rural-urban migration in India. The authors first point out that the rural-urban migration rate is relatively low in India compared to other similar countries. The explanation for this is the presence of well-functioning rural informal insurance markets. In order for these informal markets to function well, however, mechanisms must exist to prevent households from reneging on their obligations to their network. A key way this plays out is in restrictions on mobility. This raises a question: What would happen if formal insurance were introduced? Munshi and Rosenzweig run policy simulations and find formal insurance arrangements may increase rural-urban migration. Relatedly, in a new AJAE paper, Kazushi Takahashi, Chris Barrett, and Munenobu Ikegami study how the introduction of formal index insurance affects informal risk-sharing arrangements in rural Ethiopia. They find little evidence of a crowding out of informal insurance from formal insurance products.

Week of July 16, 2018

1. Women's Empowerment: Our friends at JPAL released their long-anticipated Practical Guide to Measuring Women’s and Girls’ Empowerment in Impact Evaluations. It comes with a set of questionnaires and examples of non-survey tools that can be more effective at capturing the useful and reliable data. This new study from the U.S. Census Bureau is timely, showing that when a woman earns more than her husband they both tend to exaggerate the husband’s earnings and diminish the wife’s on their Census responses. Gender norms still shape survey responses, no matter where you are. Seems like a good time to revisit IPA’s discussions on mixed methods approaches to women’s empowerment measurement with Nicola Jones and with Sarah Baird from last year. Finally, the US House passed the Women’s Entrepreneurship and Economic Empowerment Act of 2018 this week. The bill seeks to improve USAID’s work on women’s access to finance, and is notable first because of its attention to some (not all) non-financial gender-norms constraints that impact women’s prosperity, and also because it calls for improvements to outcome measurement methods.

2. Migration: The first ever Global Compact for Migration was approved by all 193 member states of the UN last week except for the United States (Hungary is now saying it won’t sign the final document), and one of its 23 high-level objectives is to “promote faster, safer and cheaper transfer of remittances and foster financial inclusion of migrants.” A lot of the language in here sounds like the same old story on remittances, and I am skeptical of the laser-sharp focus on reducing prices (it calls to eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5% by 2030), promoting financial education, and investing in consumer product comparison tools that aren’t based on evidence. Dean Yang’s 2016 study on financial education for Filipino migrants failed to find any positive impact on financial product take-up or usage, for example.

3. Remittances: What about looking to the behavioral econ world to enhance the positive effects of remittances? Behavioral nudges that can leverage digital finance look promising – Harvard Business Review had a nice piece last month on Blumenstock, Callen, and Ghani’s test of mobile money defaults to save in Afghanistan. This experiment is exciting because it shows that, with the right tools, successful interventions from the developed world, like Thaler and Benartzi’s Save More Tomorrow, can achieve similar results in other contexts. Linking remittance transfers to digital finance in the receiving country can create additional opportunities to enhance impact beyond savings, for example using data for credit scoring. Here’s an op-ed from Rafe Mazer and FSD Africa on the opportunities and risks surrounding data sharing models in emerging markets.

Week of June 18, 2018

1. Migration: If you don't get the "edition" reference, I think I envy you. But I care, and in the absence of other specific ways to oppose cruelty and barbarism, I'll spend some time here sharing some useful information about migration. Such as the fact that the US has become a "low-migration" country. I think this is as significant a change to the nature of the country as the closing of the frontier, especially since so many people don't seem to realize how much migration, whether within the US or to the US from other countries, has dropped.

On to that other crucial fact about migration: it's very very good for the people migrating and doesn't harm the people who are already there. Here's the newly officially published in AER paper by Clemens, Lewis and Postel studying the effect of the end of the Bracero program which led to 1/2 a million Mexican workers leaving the country, without any detectable benefits for native workers (employers simply invested in labor-replacing technology it appears). Here's a new NBER paper on the forced migration of Poles after World War II finding that migrants invested more in human capital for three generations. That's consistent with other work that shows long-term positive, sustained effects for people who move, even those who don't have full choice. Here's a story about how migrants fleeing the US to Canada are finding employment and thriving.

If you're interested in the big picture on global migration, the 2018 OECD International Migration Outlook is out.

2. Banking: I talk a lot about the overlaps between US and global financial inclusion issues--from household finance to consumer protection to business models to regulation. So I think both of these next two items are relevant well-beyond the countries they are focused on.

First, here's New America with a new report on how local and community banks systematically charge people-of-color more for their accounts (here's the OpEd version), which doesn't exactly encourage these historically excluded populations to join the banking mainstream. Oh, and the consumer protection regulatory system is being undermined in more ways than you might realize. Not only is there direct deregulation, but recently the Supreme Court ruled that the way the SEC carries out many of its "trials" for investment fraud are unconstitutional--and the CFPB is too. Here's Arjan Schutte writing about being fired from the CFPB's consumer advisory board which, y'know, at least he's not being unconstitutional now.

On the other hand, in India, the RBI is working to turn urban cooperative banks into "small finance banks." This piece explains a bit about the history of Indian urban cooperative banks and the regulatory issues involved--it's not all good. It's worth reading for anyone thinking about productive ways forward for more inclusive banking systems.

3. Digital Finance: In most of the countries where digital financial services have made inroads among poor households, agents are playing a big role. But those agents are often basically the same folks we see running microenterprises that we can't figure out how to improve. And that probably means that their growth is being limited by the quality of services offered and decisions made by those agents.

Week of June 11, 2018

1. Household Finance: If you'll bear with me I'm going to write about household finance mostly with links to pieces about corporate finance. Corporate finance matters a lot, and it deserves the attention and resources invested in it (Channeling Willie Sutton: why do you write papers about corporate finance? Because that's where the money is). After several hundred years of lots and lots of resources and attention we've pretty much got this thing licked right? Well, maybe not the biggest questions but at least the basic questions like accounting and financial reporting, right? Right?

Here's Warren Buffet complaining about Generally Accepted Accounting (GAAP) rules being applied to his company. And here's an argument from several business school professors that GAAP rules aren't meaningful given changes in the economy--with the enticing tidbit that in many companies having a CPA, in other words having deep familiarity with the rules of corporate finance and accounting, is a disqualification for a senior-level job in the finance department. And here's Buffet again, this time with Jamie Dimon, arguing that quarterly financial reporting is broken.

Lest you think that this is some emerging consensus, here's Felix Salmon arguing they are wrong. Here's Matt Levine arguing they're wrong. And here (via Justin Fox, which we'll return to later) is a whole book about GAAP rules being wrong for entirely different reasons.

So all of this is interesting (OK, maybe not) but what does it have to do with household finance? We haven't even begun investing the kind of resources necessary to really understand household finance, but we act like we have all the important questions licked. Or at least that households should be able to, with a little financial literacy training perhaps, be able to get a grasp on their finances and make consistently sound decisions. The fact is, for the most part, we just don't know what we're talking about when we talk about household finance. Or loss aversion.

2. Digital Finance: In another brief diversion to start off an item, an astute reader pointed out that the way I had been writing about Findex made it seem like the Findex team did not have it's own report on the findings. They do, so click on it.

One read of the both the Global Findex team's report and the CFI report highlighted last week is that the promise of digital finance is largely unfulfilled. But there's still a lot of excitement over the promise in places like Egypt apparently. I found this piece particularly remarkable because I stumbled on it right after reading through the Findex analyses, and all I could think was "I don't think that data means what you think it means." Oh, and the note that moving to digital finance would allow the government to closely inspect everyone's spending habits, wheeee!

There's a different sort of excitement over digital finance in Uganda apparently where the parliament has approved taxing mobile money and social media(?!?). Apparently there was some concern that such taxes would be regressive, but some MPs objected that people shouldn't be exempted from paying taxes just because they were poor. Clearly those people don't read CGD/Vox.

In other CGD news related to digital finance, here's a piece about using blockchain in development projects--or perhaps more on point, *not* using the blockchain for development projects. There's a terrific decision tree graphic in the piece that is worth the click on its own, even though I disagree substantially with one part of it.

3. Firms, Productivity and Labor: Earlier this week I attended two days of the Innovation Growth Lab conference put on by Nesta. A number of interesting papers and research proposals were presented--the session I found most interesting was on the global productivity slowdown...