Editor's Note: I keep telling myself that I'm going to start fighting back against the tyranny of the new, but it never seems to happen. But this week I'm taking a small step by pulling stuff I've been accumulating for the last month that hasn't made it into the faiV. Plus some new stuff of course. Get ready for a link heavy faiV. And in case any of you are wondering what I look like, I'll be interviewing Fred Wherry about the sociology of debt in the United States on Tuesday, the 20th. Register to watch the live stream here.--Tim Ogden

1. Microfinance and Digital Finance: Apparently the "farmer suicide over indebtedness" hype train is kicking up again in India. That's not to imply that farmer suicides are not a serious issue. But Shamika Ravi delves into the data and points out that indebtedness doesn't seem to be the driver of suicides and so attacking lenders or forgiving debts isn't going to fix the problem. Certainly poverty and indebtedness add huge cognitive burdens to people that affect their perceptions and decisions in negative ways, including despair. Here's a new video about poverty's mental tax--there's nothing new here, but a useful and simple explanation of the concepts.

Last year (or the year before) I noted Google's decision to play a role in safeguarding people in desperate straits from negative financial decisions: the company banned ads from online payday lenders, in effect becoming a de facto financial regulator. This week, Google announced another regulatory action. Beginning in June it will ban ads for initial coin offerings (if you don't know what those are, congratulate yourself). While I'm all for the decision, it's strange for Google to conclude that these ads are so dangerous to the public that they should be banned, but not for three more months. Cryptocurrency fraudsters, get a move on! Meanwhile, the need for Google and Apple (and presumably Facebook, Amazon, Alibaba and every other tech platform) to step up their financial regulation game is becoming clearer. In an obviously self-promotional, but still concerning survey web security firm Avast found that 58% of users thought a real banking app was fraudulent, while 36% thought a fraudulent app was real. I don't really buy the numbers, but my takeaway is: people have no idea how to identify digital financial fraud. I wish that seemed more concerning to people in the digital finance world.

2. Our Algorithmic Overlords: I've had a couple of conversations with folks after my review of Automating Inequality, and had the chance to chat quickly with Virginia Eubanks after seeing her speak at the Aspen Summit on Inequality and Opportunity. My views have shifted a bit: in her talk Eubanks emphasized the importance of keeping the focus on who is making decisions, and that the danger that automation can make it much harder to see who (as opposed to how) has discretion and authority. A big part of my concern about the book was that it put too much emphasis on the technology and not the people behind it. Perhaps I was reading my own concerns into the text. I also had a Twitter chat with Lucy Bernholz who should be on your list of people to follow about it. She made a point that has stuck with me: automation, at least as it's being implemented, prioritizes efficiency over rights and care, and that's particularly wrong when it comes to public services.

I closed the review by saying that "the problem is the people"; elsewhere I've joked that "AI is people!" Well at least I thought I was joking. But then I saw this new paper about computational evolution--an application of AI that seeks to have the machine experiment with different solutions to a problem and evolve. And it turns out that while AI may not be people, it behaves just like people do. The paper is full of anecdotes of machines learning to win by gaming the system (and being lazy): for instance, by overloading opponents' memory and making them crash, or deleting the answer key to a test in order to get a perfect score. I think the latter was the plot of 17 teen movie comedies in the '80s. Reading the paper is rewarding but if you just want some anecdotes to impress your friends at the bar tonight, here's a twitter thread summary. It's funny, but honestly I found it far scarier than that video of the robot opening a door from last month. Apparently our hope against the robots is not the rules that we can write, because they will be really good at gaming them, but that the machines are just as lazy as we are.

To round out today's scare links, here's a news item about a cyberattack against a chemical plant apparently attempting to cause an explosion; and here's a useful essay on our privacy dystopia.

3. US Poverty and Inequality: Definitely just trying to catch up here on things that have been building up. Here's a new paper on studying income volatility using PSID data, with a review of prior work and finding that male earnings volatility is up sharply since the Great Recession. There's been a bunch of worthwhile things on US labor force participation in the last few weeks. First here's Abraham and Kearney with "a review of the evidence" on declining participation. Here's a comparison of the UK and US considering why US has fallen behind in participation from Tedeschi. And here's a story from this week about how falling unemployment is affecting hiring and participation.

Returning to the theme of volatility, here's a short video from Mathematica Policy Research on how income volatility affects low-income families. Jonathan is following up on the US Financial Diaries research into income volatility and looking at how it disproportionately affects African-American households, and interacts with the racial wealth gap. But it turns out that even though African-American households are disproportionately income, asset and stability poor, they are even more disproportionately depicted as poor in media.

4. Social Investment and Philanthropy: I mentioned above that you should be following Lucy Bernholz. Via Lucy, here's a report on the massive challenge of digital security for civil society organizations. I'll take a moment to editorialize--funders are way way behind in recognizing how big a change digitization is when it comes to their own and nonprofits operations. It's not just security, though that's likely the first place that a crisis will strike. But beyond that, it's crazy that major foundations do not have CIOs on their boards of directors, and that grant applications don't include a technology infrastructure review. The ability to use technology is already a major factor in nonprofits ability to have an impact (either directly by how they deliver services or indirectly in how they can track their activities and improve), while most funders are still viewing IT as an overhead cost to be minimized. That has to change.

In other worrying trends in philanthropy that aren't getting enough attention--the explosive growth of Donor Advised Funds continues. Recently information about Goldman Sachs' DAF leaked--which is significant because part of the reason DAFs are popular is because they shield information about who donors are. Which makes it particularly interesting that Steve Ballmer and Laurene Powell Jobs, and others among the list of wealthiest people in the world are using Goldman's DAF, because the justification for DAFs is allowing those not wealthy enough to fund their own foundations to gain some of the benefits. Sounds like a gaming of the rules that an AI would be proud of.

5. Methods and Statistics: I feel like I couldn't show my face around here anymore if I didn't link to the world's largest field (literally) experiment. It was in China of course. I feel like this instance satisfies all of the objections raised by Deaton or Pritchett or Rozenzweig, but I'm sure I've missed something. By the way, anybody else have a feeling that relatively soon people are going to be questioning the importance of any study that wasn't done in China or India?

So you better jump on the chance to read about how to measure time series share of GDP in the United States (and how hard it is to say anything about manufacturing's changing role in the economy). After all it only affects about 350 million people, not enough to really care about.

Meanwhile, Andrew Gelman of all people makes the case for optimism about statistical inference and replication. I'm not sure of whether to interpret the kerfuffle over Doleac and Mukherjee's paper on moral hazard and naloxone access as bolstering or undermining Gelman's point. I'm going to choose to be optimistic for now though, against my nature.

And finally, here's a visual, interactive "textbook" on probability that has some really cool stuff. But I don't think what it's doing is going to help the problem of people not understanding causal inference.

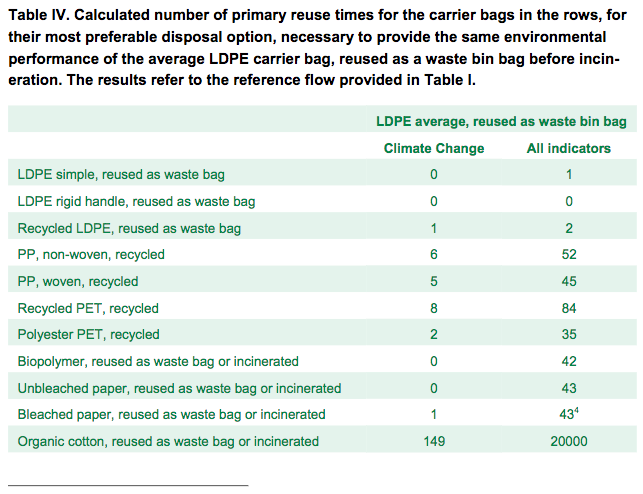

Figuring out how to do the right thing is hard. This table is from a Danish government study of climate change impact of various methods of carrying stuff. Apparently if you properly use, re-use and dispose of a standard plastic bag, it has much less climate impact than reusable cotton bags. If I'm interpreting it correctly, it means that you'd have to use an organic cotton bag something like 20,000 times before net climate impact was the same as the plastic bag's. Of course, that all depends on whether the plastic bag is properly used and disposed of. I bet neither estimate incorporates virtue compensation.